原創(chuàng) 悉尼大學(xué)商務(wù)見解

了解更多國際內(nèi)幕,請點擊下方加關(guān)注,如文章引起大家共鳴,請點贊并轉(zhuǎn)發(fā),以支持我繼續(xù)分析創(chuàng)作,謝謝了:

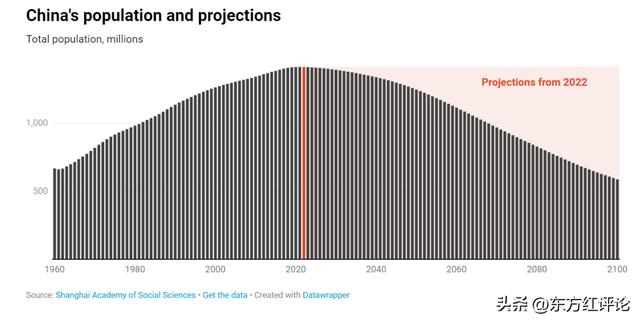

After four extraordinary decades in which China’s population has swelled from 660 million to 1.4 billion, its population is on track to turn down this year, for the first time since the great famine of 1959-1961.

繼中國人口在過去四十年間從6.6億猛增到14億之后,中國的人口今年有望下降,這是其自1959-1961年大饑荒以來首次出現(xiàn)人口下降。

The world’s largest nation by population is starting to shrink.

世界上人口最多的國家人口規(guī)模開始縮小。

In 2021 China’s population grew by 480,000 – which is a baby sized increase compared to the annual growth rate of around eight million common a decade ago.

2021年,中國人口凈增長48萬人,與十年前大約800萬的年增長率相比,這只能算是小規(guī)模增長。

For international comparison, China’s fertility rate (births per woman) was just 1.15 in 2021 compared to 1.6 in Australia and the US, and 1.3 in Japan which has been aging for decades now. In Nigeria the average births per woman is 5.2. The continent of South America, which in the middle of last century had the world’s highest population growth, is now growing more slowly than Africa, Oceania and Asia.

與國際水平相比,2021年,中國的生育率(每名婦女的胎數(shù))僅為1.15,而澳大利亞和美國的生育率為1.6,而已經(jīng)老齡化數(shù)十年的日本的生育率為1.3。尼日利亞的平均生育率為5.2。南美洲大陸在上世紀(jì)中葉曾經(jīng)是世界人口增長最快的大陸,但其目前的人口增長速度比非洲、大洋洲和亞洲都要慢。

A loosening of China’s one child policy in 2016 and the introduction of a three-child policy, supported by tax and other incentives, have failed to halt the baby dive.

2016年,中國宣布放松獨生子女政策,后續(xù)又引入由稅收和其他激勵等配套措施所支持的三孩政策,但這些舉措都未能阻止其嬰兒出生率跳水。

The Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences team predicts an annual average decline of 1.1% after 2021, pushing China’s population down to 587 million in 2100, less than half of what it is today.

上海社會科學(xué)院團隊預(yù)測, 2021年之后,中國人口將年均下降1.1%,到2100年,中國的人口將下降到5.87億,不到今天的一半。

The implications are serious: while there are currently 100 working age people supporting every 20 elderly people, by the turn of the century 100 working-age Chinese will have to support as many as 120 elderly Chinese.

這意味著嚴(yán)重的后果:雖然目前每20名老年人由100名適工年齡人群負責(zé)贍養(yǎng),但到了本世紀(jì)末,100名適工年齡中國人將不得不贍養(yǎng)多達120名老年人。

And China is far from alone: this phenomenon is in-keeping with the demographic change megatrend which predicts that the world’s population will peak by the end of this century. The combination of people living longer and having fewer children is a global experience, with the exception of Africa.

中國并非個例:這種現(xiàn)象符合人口變化的大趨勢,據(jù)預(yù)測,世界人口將在本世紀(jì)末達到峰值。除非洲之外,壽命延長和生育下降是一個全球性現(xiàn)象。

Additionally, it’s China’s economic heft that makes this an important issue for the rest of the world. Any shift in China’s economic priorities – spending more on pensions and health care, higher wages, will inevitably change what it imports, produces and exports. As the world’s single biggest trading partner, every other nation in the world will have to adjust to China’s policy settings.

此外,中國的經(jīng)濟實力使之成為世界其他地區(qū)所面臨的一個重要問題。中國經(jīng)濟重點的任何轉(zhuǎn)變(例如,在養(yǎng)老金和醫(yī)療保健方面的更多支出、更高薪酬)都將不可避免地改變其進口、生產(chǎn)和出口。作為全球最大的貿(mào)易伙伴,世界上的所有其他國家都將不得不適應(yīng)中國的政策環(huán)境。